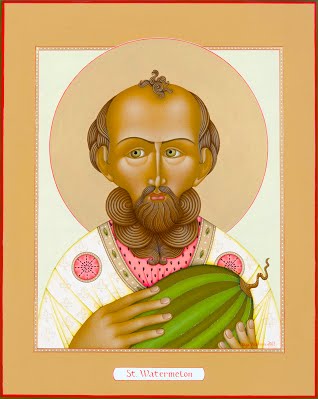

From the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art, at the University of Oregon in Eugene, Oregon,

on exhibit from September 16, 2015 to June 13, 2016:

OLGA VOLCHKOVA

The Nature of Religion Trained as an icon painter and conservator, artist Olga Volchkova (American, born Russia, 1970) uses her knowledge of Orthodox iconography and her love of botany to create provocative paintings that explore traditional icon writing and the history of florae. Iconographic types become universal symbols through which to explore the interconnectedness of humans with both the spiritual and the natural worlds. By conducting intensive research about each plant specimen she portrays, Volchkova creates visual narratives that explore the mythologies humans have created around plants. In her complex compositions, she expertly renders imagined saints, which personify each plant, as well as the form of each leaf, petal, and tendril. She depicts all manner of plant life: decorative types, such as lilies, peonies, and roses; edible specimens, such as vegetables, fruits, herbs, and plants with purported medicinal properties; as well as potentially toxic examples, such as belladonna and datura. Often quoting passages from medieval manuscripts in her paintings, she succinctly details each plant’s long history and illustrates unique attributes.

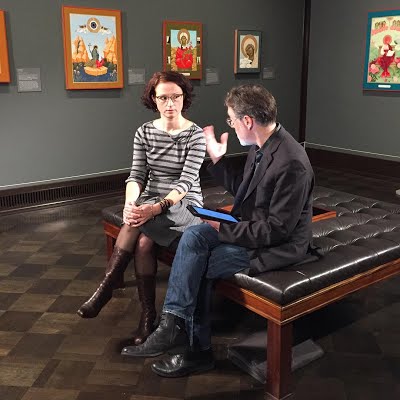

Saint Saffron Saffron, one of the costliest substances in history, is derived from the dried stigmas of

the Crocus sativus plant. In addition to its medicinal uses, saffron has been utilized as

a dye, perfume, and spice in many cultures worldwide for nearly four millennia.

Volchkova references its cosmetic applications and its strong scent in this piece.

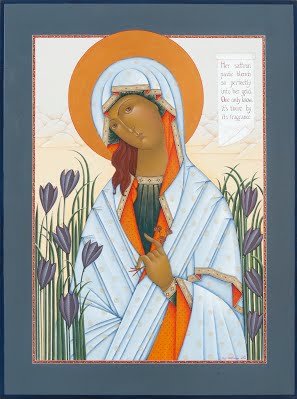

Saint Cyani Although still drawing on the tradition of Orthodox iconography, Volchkova also evokes the Renaissance trope of setting a thoughtful figure in nature in Saint Cyani. The young man in this painting grasps a bouquet of cornflowers against the backdrop of a wheat field, where the flowers grow readily. Cornflowers have recurred prominently in art for millennia. Representations of the

bright blue flowers have been found on ancient Egyptian earthenware vessels as well

as on the walls and floors of palaces. The flowers were also used in Egyptian funerary

practices, where they were revered as symbols of life and fertility and were thought

to aid the pharaohs in the afterlife. In the West, cornflowers came to be associated

with Mary, Queen of Heaven, and were portrayed often in Christian frescoes.

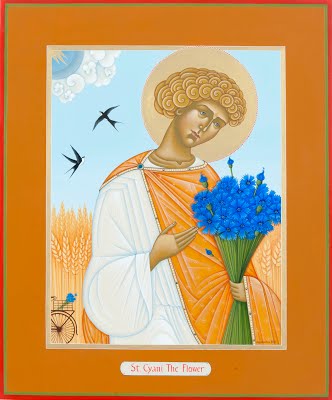

Saint Watermelon The watermelon, or Citrullus lanatus, is thought to have originated in the Kalahari

Desert, in present-day Namibia. The first recorded harvest took place in Egypt some

5,000 years ago and is recorded in ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics. Watermelons,

which are in the same family as cucumbers, pumpkins, and squash, were coveted by

other ancient empires in Europe and Asia for their refreshing flesh. Here, the artist

evokes the colors of the watermelon—the white of the pith, the pink of the

mesocarp, and the black of the seeds—in the figure’s robes, while the shades of

green in his eyes echo the stripes of green in the melon he grasps.

Super Potato In Super Potato, a six-armed figure rendered in the manner of a Russian Orthodox

saint embraces a llama, signifying the potato’s origins in the Southern Cone nearly

10,000 years ago. One hand holds a sprig of light pink and white potato flowers,

revealing their more delicate and beautiful side, while another grips a spade in

recognition of the potato’s significance to world agriculture. A third hand holds a

potato with satellite antennae, representing the fact that the potato was the first

plant to be cultivated in space. Taken together, the elements of the painting attest to

the transcultural importance of this simple root vegetable and tell of its impact on the

landscape, as well as on animal and human life.

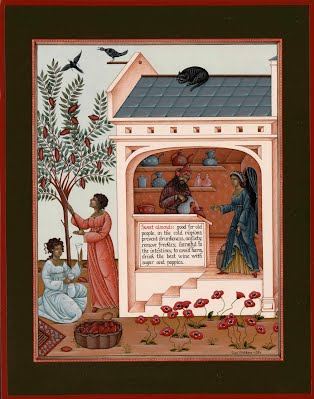

Sweet Almonds This composition more closely resembles a manuscript painting or a Renaissance

miniature than an icon. A female figure to the left tends an almond tree, with its

signature silvery green foliage. In the biblical context, almonds are often associated

with old age and aging because of their leaf color and their gnarled limbs. The text in

this work suggests that folk remedies featuring almonds were also thought to have

curative properties for the elderly.

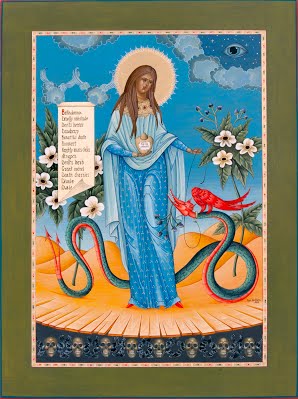

Santa Belladonna As the scroll along the left side of this painting suggests, Atropa belladonna—a

member of the nightshade family—is commonly known by a number of different

names. Many reference death or the devil as both the berries and foliage of the

deceptively sweet-looking herb are extremely toxic. A single leaf can prove fatal. The

plant’s most common name, belladonna, meaning “beautiful woman” in Italian,

references the use of the herb by women to enlarge their pupils.

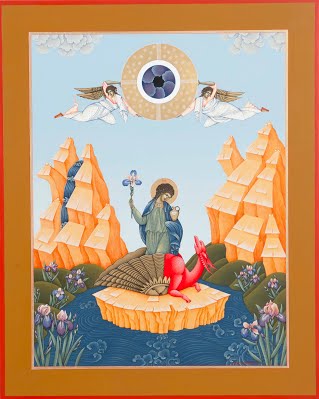

Saint Datura Datura, commonly called devil’s snare or devil’s trumpet, is a member of the

nightshade family, which also includes the potato and the tomato. It originated in

parts of present-day Mexico and the Southwestern United States, although it was

introduced to areas of South America and South Asia during the first millennium CE.

Datura has long been recognized for its hallucinogenic and medicinal properties.

Volchkova references its ability to induce visions by substituting the head of the saint

with one of the flower’s blossoms. The enlarged pupil of the all-seeing eye in the

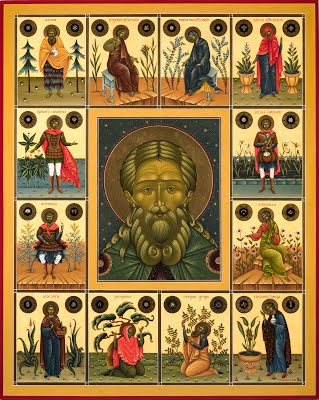

upper left corner also alludes to the psychotropic effects of the plant. Holy Spirit of Herbs Twelve figures representing natural antibiotics form what Volchkova identifies as the

Holy Spirit of Herbs. The painting appropriates a common style for festival icons and

other large icons with a unifying theme, where twelve smaller compositions frame the

central figure. Clockwise from the upper left, the saints along the edges of the work

represent lichen, ginger, rosemary, sage, garlic, Echinacea, turmeric, Oregon grape,

juniper, aloe vera, wormwood, and goldenseal.

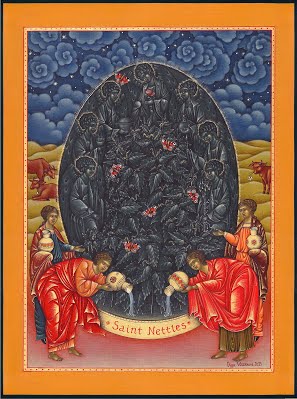

Saint Nettles In Orthodox iconography, both heavenly and earthly spheres are often depicted

within a single composition. In this work, the heavenly realm is located within the

mandorla, or the light-radiating shape enclosing the winged figures. Each of the

figures demonstrates a common use of the plant, which can be made into cloth, used

as a natural green dye, or employed in a number of medicinal remedies.

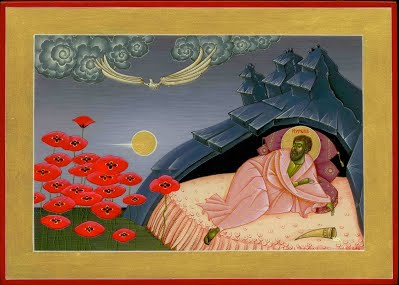

Saint Hypnos Hypnos, the Greek god of sleep, was the son of the goddess Nyx (Night) and the

brother of Thanatos (Death). He is often represented with a horn of poppy juice,

slumbering in an open cave surrounded by opium poppies, being soothed to sleep by

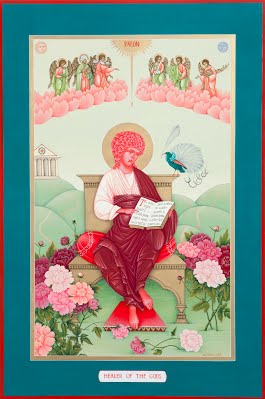

the sound of the river Lethe, the underworld river of forgetfulness. Paeon Many gods in the Greek pantheon are associated with healing and medicine. One of

these, Paeon, is known as the healer of the Olympian gods. In verses 401 and 899 of

Homer’s Iliad, Paeon applies soothing herbal ointments to heal first Hades and then

Ares. In this work, Volchkova portrays the healer’s many patients in the floral clouds

at the top of the painting. The titular character is seated on a throne nestled among

the flowers named for him. In his hands, he holds a book enumerating some of the

flower’s medical applications.

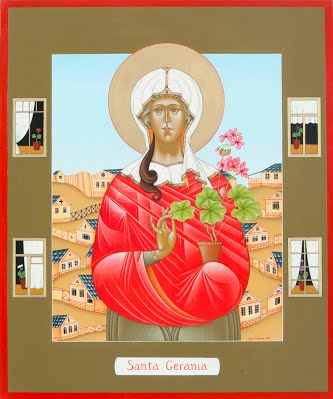

Santa Gerania The name for the genus of flowers to which the geranium belongs originated from the Greek word for crane, which is géranos, because of the fruit capsule’s resemblance to a crane's bill. Geranium plants have grown wild in Europe for thousands of years and have been cultivated there to be used in herbal remedies since the medieval period. The plant boasts properties that stop bleeding and tighten tissues and is often used externally to treat minor wounds. As they are hearty plants that can survive harsh winters, they are also used decoratively in cold climates, such as Russia. Volchkova notes that these flowers provide hope during the winter months in even the most humble of Russian homes.

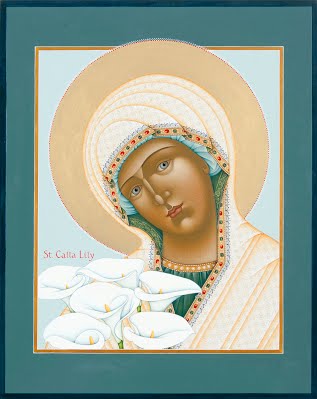

Saint Calla Lily Calla lilies were imported to the United States from South Africa in the mid-19th century. The exotic flowers became immensely popular in the art world of the early 20th century as Imogen Cunningham, Georgia O’Keeffe, Diego Rivera, and Edward Weston provocatively represented them in their photographs and paintings. Despite the many sexual interpretations of the calla lily’s form in modern art, the flower has been traditionally associated with purity.

Saint Iris This flower is named for the Greek goddess Iris, who, according to the poet Hesiod,

was the daughter of the sea god Thaumas and the ocean nymph Electra as well as a

sister to the harpies. She was a messenger of the gods and an enforcer of oaths. As

oaths among the gods were sealed with water from the River Styx, Iris perpetually

carried a ewer of water from the river, which was said to render liars unconscious for

one year. Iris is typically portrayed with her ewer and a herald’s staff. Here, her staff

takes the form of the flower named for her.

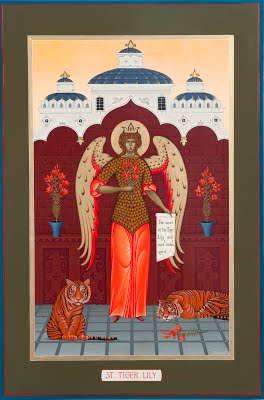

Saint Tiger Lily The tiger lily, or Lilium tigrinum, is native to China, where it symbolizes friendship and prosperity. William Kerr introduced it to Britain in the early 19th century, along with hydrangeas and peonies. For the first Westerners who encountered the bold orange flower at Kew Royal Botanic Gardens in London, it embodied the Orientalist fantasies of exoticism and mystery in the Far East. The artist references these associations with the lounging tigers at the winged figure’s feet. The shape of the petals is mirrored in the architectural details of the palace in the background. In the text of the scroll held by the angel, which suggests that the flower’s scent will cure a “violent spirit,” Volchkova also notes the tiger lily’s importance to Chinese traditional medicine.

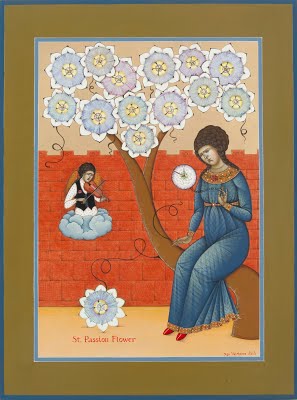

Saint Passionflower The passiflora, or passionflower, is a vine native to parts of Argentina, Brazil, and Paraguay. Its modern Latin name derives from the supposed resemblance of the flower’s corona to the crown of thorns Christ wore during his Passion, or the period between his arrest in the Garden of Gethsemane and his crucifixion on Calvary.

Similarly, the tendrils have been said to represent the scourging of Christ, while the

stigma is said to represent the nails that pierced his hands. Early Catholic missionaries

to the Americas, who would have been encountering the plant for the first time, used

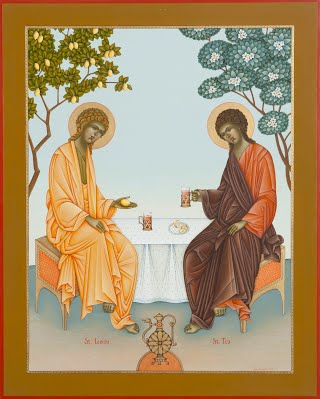

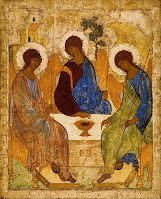

the flower to illustrate the sufferings of Christ to the indigenous peoples. Saint Tea and Saint Lemon The seated figures of Saint Tea and Saint Lemon in this work pay homage to the Russian monk and painter Andrey Rublyov’s famous Trinity icon of the early 15th century. Rublyov’s composition includes three seated figures; they are the angels who visited Abraham at the oaks of Mamre, according to the biblical account in Genesis, chapter 18. While Volchkova’s work has only two figures, their arrangement at the table—even including the position of their feet—is a clear allusion to Rublyov’s distinctive piece. Tea was first cultivated and oxidized in the vicinity of the Sichuan province in China

approximately four thousand years ago. This is the same general region and time

period in which the lemon was domesticated. Here, the saints take their tea with

lemon from podstakannik, which are ornate metal vessels with handles, used for

holding very hot beverages. In the foreground is an intricate tea samovar, used for

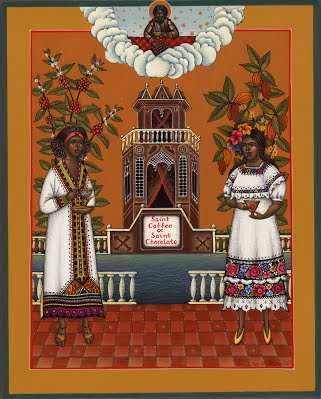

boiling water. Andrey Rublyov (Russian, circa 1360 – 1430) Trinity, early 15th century Saint Coffee and Saint Chocolate Icons often feature two or more saints that are in some way connected. Volchkova draws on that tradition here with two of the most sought-after crops in history—cafea and cacao, from which coffee and chocolate are produced. In the upper left is the cafea bush, native to Ethiopia. In the upper left is the cacao tree, native to Mexico. Note that the saints wear the traditional garb of the regions from which these

valuable crops came.

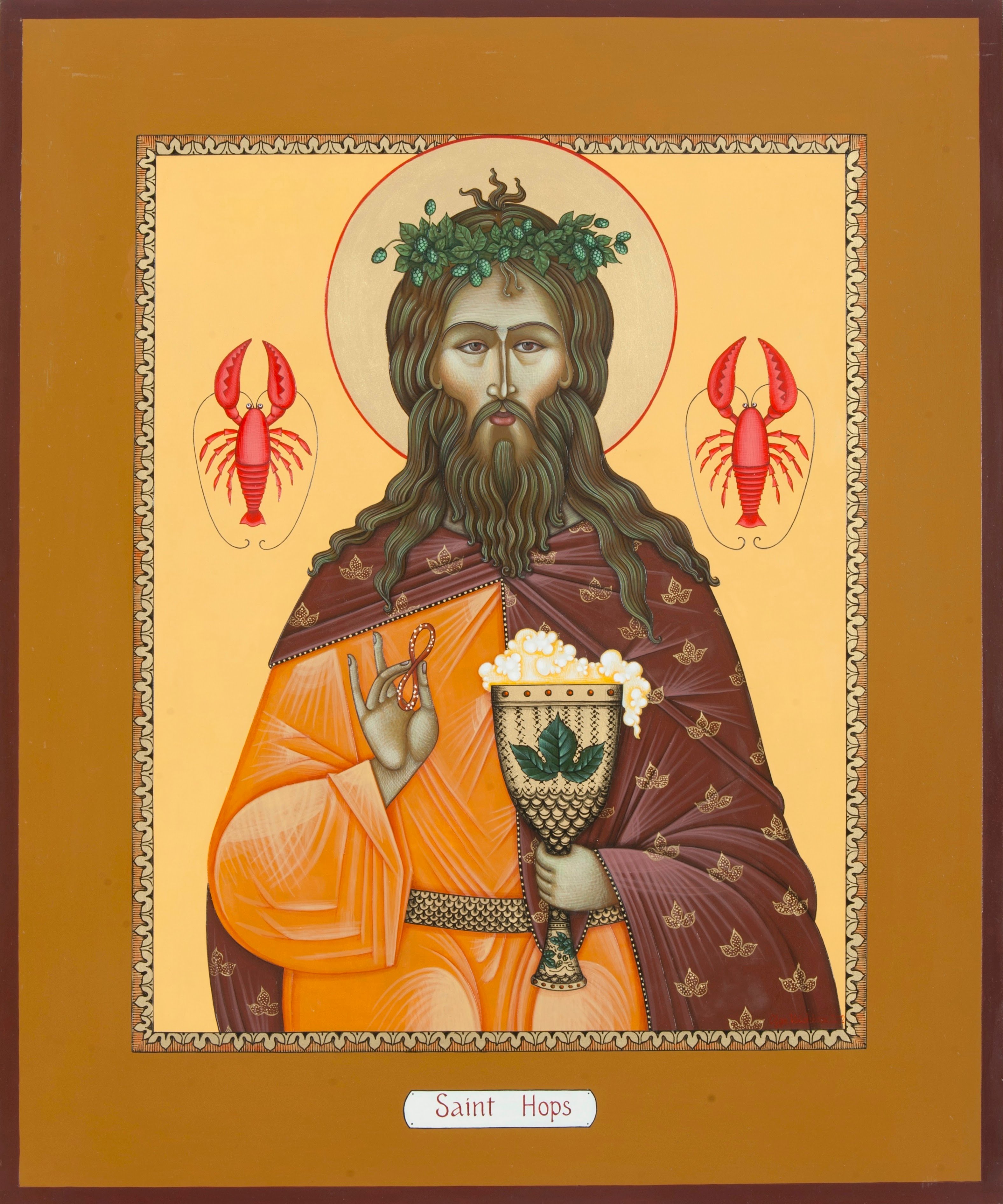

Saint Hops The flowers of humulus lupulus, or hops, have been added to beers during the

brewing process as a flavoring agent since the medieval period, if not earlier. In

Russia, pretzels and crawfish traditionally accompany beer. Volchkova has noted that

the infinity pretzel in this painting is meant as a token for Saint Hops, in gratitude for

the revival of local brewing throughout the world.

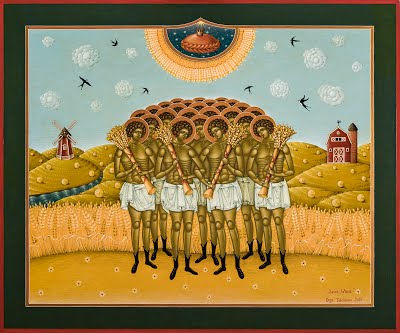

Saint Wheat Wheat is grown on a greater land area that any other crop globally. The cultivation of wheat, which may have begun as early as 10,000 BCE, marked the beginning of systematic agriculture and dramatically changed food and eating worldwide. One of the principal benefits that grew out of the cultivation of wheat was the invention of bread. Both leavened and unleavened types are mentioned often in the Old and New Testaments of the Bible. Even Christ is referred to as the “living bread that came down from heaven” in the gospel of John. Text by June Black and Greg Bryant. With thanks to the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art and the University of Oregon.

|

|

|